Trump Media’s auditing firm, BF Borgers, busted for “massive fraud”

Posted on

On May 3, 2024, the Securities and Exchange Commission announced an enforcement action against auditing firm BF Borgers CPA PC and its principal, Benjamin F. Borgers. The regulator charged the firm with “deliberate and systemic failures to comply with Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) standards in its audits and reviews incorporated in more than 1,500 SEC filings from January 2021 through June 2023.” Moreover, Borgers assured its many clients that their work was compliant with PCAOB standards when that was not the case, and went so far as to fabricate documentation to make it look as if PCAOB standards had been met.

Gurbir S. Grewal, director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, called the matter “one of the largest wholesale failures by gatekeepers in our financial markets,” adding that:

As a result of their fraudulent conduct, they not only put investors and markets at risk by causing public companies to incorporate non-compliant audits and reviews into more than 1,500 filings with the Commission but also undermined trust and confidence in our markets. Because investors rely on the audited financial statements of public companies when making their investment decisions, the accountants and accounting firms that audit those statements play a critical role in our financial markets. Borgers and his firm completely abandoned that role, but thanks to the painstaking work of the SEC staff, Borgers and his sham audit mill have been permanently shut down.

Benjamin Borgers and the firm agreed to settle the charges. BF Borgers will pay a $12 million civil penalty and Benjamin Borgers will pay a $2 million civil penalty. Both are immediately suspended from appearing or practicing before the Commission.

According to the SEC’s order, between January 2021 and June 2023, Borgers had had 350 clients who were required to incorporate audited financial statements into the annual reports they submitted to the Commission, and were further required to review quarterly financial reports submitted by those clients to the Commission. Borgers assured the issuers that the work he did would comply with PCAOB standards, but it did not. He failed to supervise and review the work done by the engagement teams, did not conduct or participate in audit planning meetings, and did not review workpapers produced by the teams. In fact, he allowed his staff and contractors to copy materials from old audits and reuse them in new ones. All that is particularly disturbing given his large number of clients:

Among other things, PCAOB Auditing Standard 1220: Engagement Quality Review (“AS 1220”) requires audits and reviews of interim financial information to be approved by an engagement quality reviewer (“EQR”). Despite this clear requirement, Respondents failed to obtain an EQR to provide a concurring review and approval on audits and reviews of financial statements incorporated in at least 1,625 public filings and disclosures from January 2021 through June 2023, including over 336 SEC issuer annual filings, 1,039 SEC issuer quarterly filings, 180 SEC registration statements, 45 SEC-registered broker-dealer annual filings, and 25 OTC company annual report disclosures, representing at least 75% of their clients’ public filings and disclosures incorporating such audits and reviews.

These findings will create ongoing problems for Borgers’ clients. As the SEC put it, Borgers’ actions “caused audit clients to violate certain provisions of the Exchange Act and rules thereunder…” The regulator also issued a statement offering guidance to issuers who’ve used Borgers as their auditor. In terms of formal measures, they’ll have to fire Borgers formally, and/or he will have to resign. Both must file with the SEC to report what has happened.

Unfortunately for the issuers, that is not the end of it. All the Borgers clients will need to find new auditors, and they will have to restate their financials going back to at least January 2021. That will be difficult and expensive for those who lack deep pockets. The consequences will be like those experienced by the issuers serviced by Moore & Associates Chartered back in 2009. Moore had more than 300 clients, most of them OTC issuers, and the engagement teams he employed were staffed by “high school graduates with little or no education or experience in accounting or auditing.” Since Moore had so many clients, the sanctions imposed by the SEC caused a logjam in the system: many were unable to find new auditors, or new auditors they could afford, and ended up deregistering by filing a Form 15. We believe it’s likely quite a few of Borgers’ clients will do the same.

Who is Borgers?

We’ve been taking an interest in BF Borgers for a while now. The company was formed in Colorado in 2009. It’s based in Lakewood, a suburb of Denver. Ben Borgers and his staff work out of an older single-story building.

Perhaps surprisingly, the business hasn’t yet got around to killing its website. On the “About Our Firm” page, Borgers promises that “professionalism,” “responsiveness,” and “quality” are the company’s bywords. On the “Meet Our Team” page, the only team member featured is Ben Borgers himself.

He didn’t start out badly. A graduate of Texas A&M, he first worked for Grant Thornton, where he was assigned to a job involving forensic accounting. Eventually, he opened his own firm and has been working on expanding it since then. He seems to have his eccentricities, however: the Financial Times recently reported that he’s spelled his name 14 different ways in filings with the PCAOB. Some may be genuine mistakes, but others—like Ben F Vonesh—suggest deliberate deception.

He registered with the PCAOB in May 2010 and has kept up his registration. His most recent Form 2 annual report, from 2023, shows that in the previous year, the firm had 50 personnel, all of them accountants. Of them, 10 were CPAs, and four were authorized to sign the firm’s name on audit reports. The 2022 report shows that in 2021 staff was the same, except that 15 of the accountants were CPAs. The 2021 report shows that in 2020, there were 40 accountants, 20 of whom were CPAs, and the 2020 report indicates that in 2019, there were 39 personnel, made up of 35 accountants, 21 of whom were CPAs, and, presumably, four non-accountant employees.

Between 2019 and 2022, Borgers increased its number of accountants from 35 to 50, but the CPAs among them decreased from 21 to 10. That suggests a significant decline in expertise and, perhaps, in the quality of results. We’ve also made our own list of the issuers the firm serviced over the past four years. It differs somewhat from that offered on the Form 2s, in part because the forms lack the space to accommodate numbers over 100 in response to the relevant query. We conclude that in 2019, Borgers conducted audits for 95-100 issuers; in 2020, for approximately 135 issuers; in 2021, approximately 160 issuers; and in 2022, approximately 170 issuers. As the number of staff CPAs was cut in half, the number of clients ballooned.

Borgers is, in fact, now the eighth-largest audit firm in the country by number of clients. The Financial Times recently reported that according to Ideagen Audit Analytics, Ben Borgers “is now the most prolific individual auditor of U.S. public companies, personally signing 143 public company audit opinions in the past year… five times more than any other US accountant.”

Other Regulatory Problems

Today’s action, which will remove BF Borgers and its founder from the auditing business forever, was a long time coming. In recent years, PCAOB inspections turned up consistent deficiencies, and disciplinary actions have been taken against several of its employees.

The PCAOB’s 2022 report, released on November 7, 2023, suggested that the firm’s problems were serious. It covered the years 2019, 2021, and 2022 (2020 was probably skipped due to the COVID-19 pandemic), and the inspectors examined 9, 10, and 11 audits from those years, respectively.

Of those, only one audit was not deficient. This dismal performance makes the dramatic increase in the number of Borgers’ clients even more puzzling, given that most issuers forced to restate their financials will likely find a new auditor.

In addition, 11 of the 11 audits reviewed in 2022 had multiple deficiencies, as did 10 of the 11 reviewed in 2021, and 7 of the 9 reviewed in 2019.

The 2021 inspection report is similar. Ten audits were reviewed, and all were found to contain notable deficiencies. Embarrassingly, the PCAOB found Borgers was one of only 12 firms from that inspection year that failed to address quality control satisfactorily.

The report was extremely critical. “The firm significantly increased its number of issuer audit clients … without a corresponding increase in the number of firm partners.” The PCAOB also criticized the “tone at the top” of the firm and said Borgers’ management “lacks the necessary commitment to undertake only those engagements that it can reasonably expect will be completed with professional competence.” The report concluded: “Leadership does not appear to be sufficiently balancing firm growth with ensuring audit quality.”

These comments are especially important because of the effect they might have on Borgers’ clients. For the most part, those clients are not large, successful companies. Many are startups trading on the OTC. They don’t have money to spare. While Borgers is not as expensive as some auditors, he isn’t cheap, either. The issuers who turned to him should have had a right to the “quality” work he promised.

The 2021 report also noted that:

The firm significantly increased its number of issuer audit clients from 80 in 2019 to 168 at the outset of the 2021 inspection (or by 110%). In accepting these new clients, the firm did not take into account the level of proficiency required for the firm’s partners in the circumstances as well as competing time demands on the partners assigned to lead and execute the audits and perform the engagement quality reviews for all of its issuer audits. For example, during the year, there was one engagement partner who was responsible for 147 issuer audits. Further, there was one engagement quality reviewer who was responsible for 103 issuer audits and another who was responsible for 74 issuer audits. In addition, in one audit included in Part I.A,3 a significant number of work papers related to several areas of the audit were prepared and/or reviewed subsequent to the report release date.

Does the part about the workpapers that were prepared after the report was released describe what the SEC called the “fabrication” of workpapers? That’s not all: the report is 25 pages long and has nothing good to say. It closes with an observation that Borgers had audited six firms whose principal executive offices were in states that required registration or licensure by auditors working in them. Borgers was not, and still is not, licensed anywhere but Colorado and Canada. The firm had the opportunity to respond to the criticisms in that and other reports but chose not to do so.

Earlier inspection reports paint the same dismal picture. Two company employees were disciplined individually by the PCAOB. Bo-Shiang (“Eric”) Lien, a CPA, was found to have failed to comply with PCAOB “rules and standards” in multiple instances between 2017 and 2019. In May 2022, he was fined $25,000 and barred from association with registered public accounting firms. In 2019, Brady Jensen, also a CPA, was suspended from working for a public accounting firm for one year, and formally censured by the PCAOB.

The firm has also had problems with the State Board of Accountancy of the State of Colorado. The board found that Borgers had signed audits in South Carolina although he was not licensed or registered to work there, and the accountant he’d assisted was not licensed or registered to work in Colorado. He got off easily, with a Letter of Admonition and a small fine. More recently, in March 2024, the board went after him again, this time for failing to conduct at least some of his audits according to generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS), failing to exercise due care in the performance of his professional services, and failing to meet generally accepted accounting principles or generally accepted auditing standards in the profession. Despite that, the only sanctions applied were another Letter of Admonition and a $5,000 fine.

Borgers wasn’t getting into trouble only in the U.S. In late 2023, the Canadian Public Accountability Board found the firm—which, remarkably, had acquired the greatest number of new engagements in Canada in 2022—was registered with the CPAB but did not, the organization found, follow its rules. It was duly censured and barred from taking on new Canadian clients.

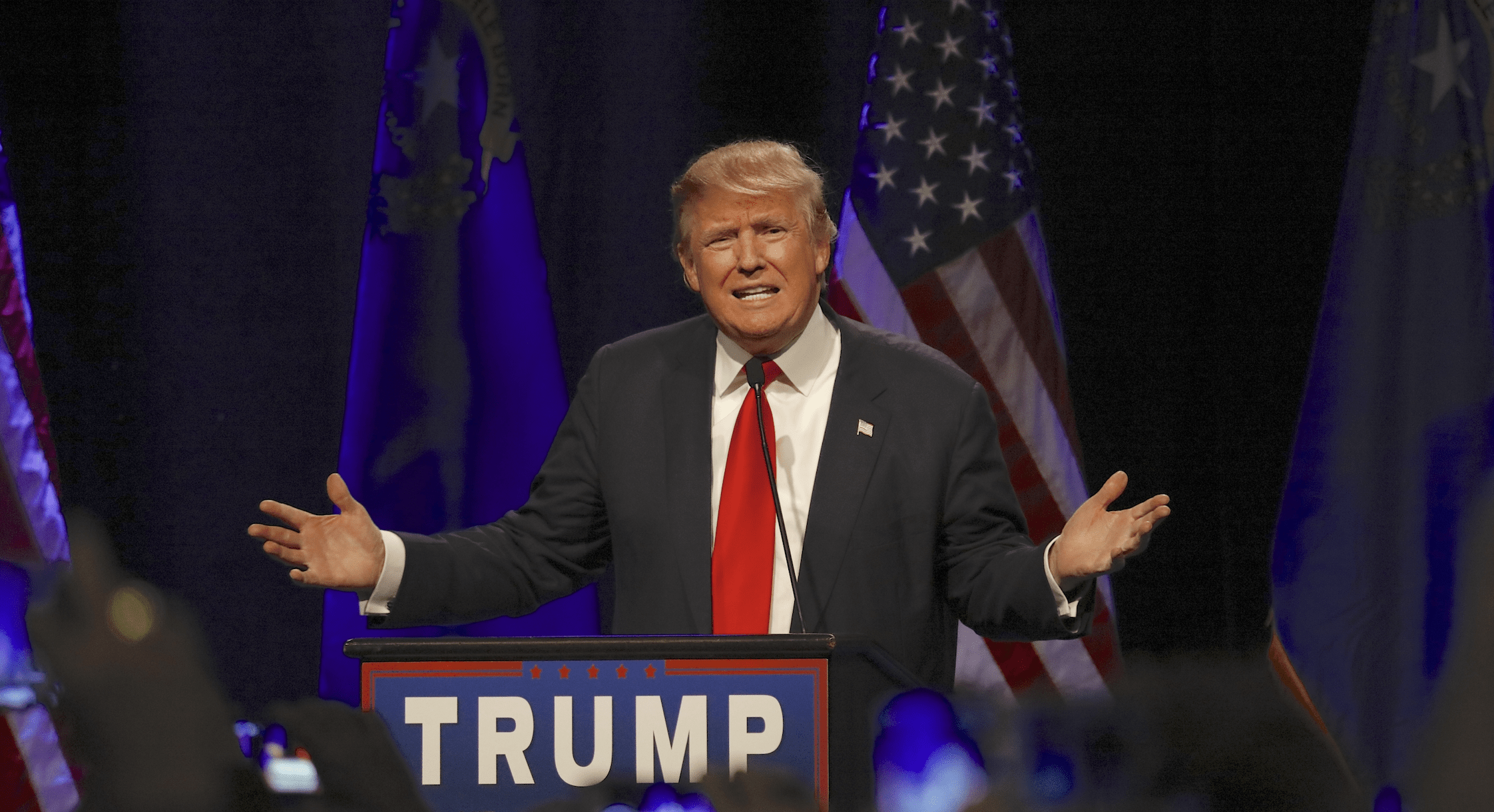

BF Borgers and Trump Media & Technology Group

While Borgers once worked for a great many issuers over the years (see the list at the end of this article), few of them were large or prominent. When he struck out on his own in 2009, his clients mostly traded OTC. But more recently, no doubt, in response to the changes to Rule 15c2-11, he added a number of Nasdaq Capital Market companies and some SPACs. His most prominent client was not itself a SPAC, but it was destined to merge with one. It was Trump Media & Technology Group (known as TMTG, and now trading as DJT).

The “reverse acquisition” of TMTG and a SPAC called Digital World Acquisition Corp (DWAC) closed on March 25, 2024. The closing was the end of a longer-than-expected journey to public status for the new entity, and—for those involved in the transaction—the hoped-for beginning of a long and successful run as the operator of a social media site called Truth Social that will rival Elon Musk’s X and its competitors. The company also plans to launch a live-streaming service featuring entertainment programming, news, podcasts, and more.

DJT already had problems. Nine months ago, DWAC was charged by the SEC with “material misrepresentation” to its investors. More recently, Patrick Orlando, SPAC manager and CEO of DWAC, has sued TMTG, saying he’s entitled to more stock; TMTG’s two founders, Andrew Litinsky and Wes Moss, are suing Trump Media, saying they’ve been denied shares owed to them, and TMTG is suing Litinsky, Moss, and Orlando. Many observers doubted the merger would ever be completed. Now, thanks to the SEC’s action, the new public company has no auditor.

Once upon a time, a company run by someone so prominent as a former president would have gone public in a traditional IPO. It appears, however, that Donald Trump wanted to move quickly, but he seems also to have wanted to avoid the sleaziness that attaches to a no-frills reverse merger involving a public shell. He evidently wanted to be able to raise some money as well as go public. And so he decided on a merger with a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC).

SPACs are a refined version of the registered shell companies of the past. They’re new entities, not old ones with, perhaps, shady histories. They seem to have acquired their new name in the wake of the dot.com crisis. In the past, these mergers had almost always created companies that would trade OTC. But in 2005, the American Stock Exchange (now the NYSE Amex) surprised the still-skeptical SEC by agreeing to list SPACs. Three years later, in early 2008, the Nasdaq and the NYSE followed suit. Then came the crash that sent stocks tumbling and created chaos in the financial sector. SPACs once again fell into disfavor. They were used occasionally, but could not be called a popular alternative to a traditional IPO.

But suddenly, in 2020, SPAC initial offerings quadrupled to 248. At the time and in retrospect, it seemed likely that that had to do at least in part with the sudden appearance of the “meme stocks” and the sudden enthusiasm of retail market participants for team participation in a market they didn’t understand and didn’t want to understand. Some made out remarkably well.

Going public via SPAC can be very fast for fortunate issuers. While more expensive than a direct listing, a SPAC merger will not be as staggeringly expensive as an IPO. The SPAC’s management will have already done much of the work required. As with other ways of obtaining or creating public shells, there are specialists in the field, experienced people who’ve become known as successful SPAC managers.

The manager will usually serve as the CEO of the SPAC. He begins by incorporating the company and drawing up its bylaws. The bylaws will authorize the issuance of stock, rights, warrants, and options; he will later be free to issue the types of securities that will serve his purposes. Every SPAC needs a sponsor or sponsors. Often, though not always, the manager acts as one. The sponsor will make a nominal investment—usually $25,000—and, in return, will receive “founder shares” equal to a 20 percent interest in the SPAC. The sponsor(s) will then approach other industry professionals and ask them to act as “anchor investors.” The anchor investors will agree to invest in the offering planned by the company and will also receive an allotment of founder shares from the sponsor(s). Their investments in the IPO will be, like the sponsor’s investment, inexpensive.

The SPAC then prepares a Form S-1 initial registration statement in which it describes the offering it plans. The securities to be registered (and sold in the offering) are always “units,” generally consisting of one share of common stock and a fraction of a warrant. (Fractional warrants are preferred because they’re ultimately less dilutive than would be a unit comprised of one share of stock and one warrant.) The units will be sold to the anchor investors and to retail investors. The price of each unit will be about $10. Subsequently, the common stock and the warrants will trade separately on the open market. Sometimes the units will trade as well, but when the SPAC is, as they say, de-SPACed, the units will be cancelled.

The SPAC will say in its registration statement that it plans to seek a “business combination” with a target company. But it cannot have already chosen its target, according to SEC rules, or even have engaged in discussions with a potential target. Usually, the SPAC has up to two years to locate a target and make a deal. If at any time it falls through, investors in the IPO will be reimbursed the $10 a unit they invested.

DWAC and TMTG

Donald Trump had been interested in having his own media company for years. He’d enjoyed his years as Chairman on The Apprentice and had made nearly $500 million from it and associated promotions. Even before he lost the 2020 election, there was talk that he might choose to go up against what was then called Twitter, creating his own social media site, one where he could say whatever he pleased.

In January 2021, Trump was approached by Andy Litinsky and Wes Moss with a business proposal. They weren’t strangers: both had been contestants on season two of The Apprentice, which aired in 2004. The pair owned a Delaware company called United Atlantic Ventures, LLC (UAV). The idea was that UAV would provide services to a new company Trump would form. To that end, a “services agreement” was drawn up.

Trump first explains:

WHEREAS, the goal and mission statement of Trump Media Group Corp. is to create a conservative media powerhouse that will rival the liberal media and fight back against “Big Tech” companies of Silicon Valley...

However, Trump Media Group did not yet exist: Moss and Litinsky, acting as UAV, were to see to its formation, and to get it up and running. They are also to be entrusted with “positioning” TMTG “to access any of the private equity or public and private equity capital markets. This access may, for example, include a business combination with a SPAC.” For its work, UAV will be paid 8,600,000 shares and receive reasonable expenses. Trump, for his part, will give UAV potentially valuable intellectual property rights and will allow Litinsky and Moss to name two board members. He would receive 90 million shares of the new company’s stock.

The copy we have is attached to the lawsuit eventually filed by Trump against UAV. It’s signed by Trump acting for himself and again by him acting for Trump Media LLC, a Delaware company formed on January 28, 2021. Neither of Trump’s signatures is dated. Only Litinsky signed for UAV; his signature is dated February 2, 2021. Trump Media Group Corp. was formed shortly thereafter, on February 8. Litinsky and Moss no doubt thought they’d done well, and would make millions. What they failed to realize was that the company—Trump Media Group Corp., later Trump Media & Technology Group—was not a party to the Services Agreement, and so was not bound by any of its provisions.

In fact, only a few months later, on July 30, 2021, Eric Trump, acting for his father, notified UAV that Donald Trump deemed the Services Agreement void ab initio. UAV agreed to that. The Services Agreement was replaced by a licensure agreement that was narrower in scope than its predecessor.

Despite that, the real-life apprentices got to work immediately, though in the suit, which was filed on March 24, 2024, TMTG claims they did nothing but damage the company. We do learn from the complaint that it was they who got Patrick Orlando involved with TMTG. Orlando is a Peruvian American who’s worked in both countries and has connections in China. Orlando has managed several SPACs, though not all consummated the mergers they sought. DWAC was incorporated in Delaware on December 11, 2020. In addition to being manager, Orlando served as chairman and CEO. In 2021, the CFO was Luis Orleans-Braganza, a member of Brazil’s National Congress. The SPAC’s sponsor was ARC Global Investments II, LLC. According to the S-1 filed by DWAC to take the SPAC public:

ARC Global Investments II LLC, our sponsor, is the record holder of the securities reported herein. Patrick Orlando, our chairman and chief executive officer, is the managing member of our sponsor. By virtue of this relationship, Mr. Orlando may be deemed to share beneficial ownership of the securities held of record by our sponsor. Mr. Orlando disclaims any such beneficial ownership except to the extent of his pecuniary interest.

Litinsky and Moss also hired an auditor for TMTG, one awarded only an 80 percent deficiency rate by the PCAOB. Shortly after the formation of the company in January 2021, WithumSmith+Brown came on board. But they didn’t stay for long. On April 15 of this year, the Financial Times reported that Withum had quit before the end of the year. According to anonymous sources, “the accounting firm had decided it did not want to be associated with a business venture by the former US president.” When asked for comment, TMTG replied, “Apparently, the Financial Times’ business model is to charge its subscribers $75 per month for the privilege of reading outdated stories touting irrelevant information.” Withum was replaced as TMTG’s auditor by Borgers. The firm was hired in January 2022.

The SEC paid close attention to DWAC’s initial public offering. The S-1 went through six amendments before it was deemed effective on September 2, 2021. The company’s auditor, Marcum LLP, included the usual “going concern” warning, but that wasn’t a problem: it was, after all, a SPAC, with no business. It was time for it to find a target company, negotiate a merger agreement with it, and close the deal. It now had money with which to woo a target. Had it sold the entire offering, the company would have raised $346,725,000. It appears, however, that it did not; the proceeds, which were held in trust, were $293 million.

Work on the merger seemed to be progressing apace. In early December, a group of institutional PIPE investors signed subscription agreements worth $1 billion in committed capital, “to be received upon consummation of their business combination. Once the merger was finalized, the new company would have a good deal of cash to grow its business: with the money DWAC had raised in its IPO, the amount would be approximately $1.25 billion. That was very good news. There was good reason to believe the merger would be completed within a few months.

But something had gone badly wrong. In the same 8-K, under “other events,” a bombshell went off:

DWAC has received certain preliminary, fact-finding inquiries from regulatory authorities, with which it is cooperating. Specifically, in late October and in early November 2021, DWAC received a request for information from FINRA, surrounding events (specifically, a review of trading) that preceded the public announcement of the October 20, 2021 Merger Agreement. According to FINRA’s request, the inquiry should not be construed as an indication that FINRA has determined that any violations of Nasdaq rules or federal securities laws have occurred, nor as a reflection upon the merits of the securities involved or upon any person who effected transactions in such securities. Additionally, in early November 2021, DWAC received a voluntary information and document request from the SEC which sought, inter alia, documents relating to meetings of DWAC’s Board of Directors, policies and procedures relating to trading, the identification of banking, telephone, and email addresses, the identities of certain investors, and certain documents and communications between DWAC and TMTG. According to the SEC’s request, the investigation does not mean that the SEC has concluded that anyone violated the law or that the SEC has a negative opinion of DWAC or any person, event, or security.

Perhaps that news confirmed Withum’s uneasiness about TMTG and prompted the firm’s resignation. On December 6, 2021, the company announced that Devin Nunes had been appointed CEO of TMTG. He was currently still a sitting Congressman, but planned to resign in January 2022. It seems likely that TMTG believed Nunes’s government experience would be helpful in its dealings with the SEC and FINRA. He must also have seen to the hiring of BF Borgers, who took over as the company’s auditor in January 2022. Probably someone suggested Borgers to Nunes; he isn’t known to have had any prior experience running public companies.

Donald Trump must by then have been concerned about the delay in finalizing the merger and annoyed about the investigations. He’d originally been a company director and was described as the chairman in an SEC filing from May 1, but on June 8, 2022, he resigned from the board, along with Wes Moss (whose resignation was probably not entirely voluntary), Donald Trump Jr., Kash Patel, Andrew Northwall, and Scott Glabe. By early 2023, the last four had been reinstated.

That May 1 filing is of some importance. It’s a new S-1, whose purpose was to register up to 100,100,100 of the PIPE shares. Both Borgers and Marcum were involved in its preparation. Clearly, the investigations were continuing. In an 8-K from June 27, 2022, it’s noted that a grand jury had been empaneled in the Southern District of New York, and the Department of Justice has joined the other investigators. Note that the investigators were showing particular interest in DWAC’s S-1 filings:

On June 16, 2022, Digital World became aware that a federal grand jury sitting in the Southern District of New York has issued subpoenas to each member of Digital World’s board of directors; the subpoenas seek certain of the same documents demanded in the above-referenced SEC subpoenas, along with requests relating to Digital World’s S-1 filings, communications with or about multiple individuals, and information regarding Rocket One Capital. Additionally, on June 24, 2022, Digital World received a grand jury subpoena with substantially similar requests. These subpoenas, and the underlying investigations by the Department of Justice and the SEC, can be expected to delay effectiveness of the Registration Statement, which could materially delay, materially impede, or prevent the consummation of the Business Combination.

The investigations continued, and still the merger had not been consummated. On March 19, 2023, the board of DWAC fired Patrick Orlando from his positions as Chairman and CEO of the company. He remained a member of the board, no doubt, because he was a 10 percent owner of DWAC, as was his company Arc. Eric Swider, another director, took over his executive positions on an interim basis.

The investigations were having an effect. It seems Orlando’s firing was all about the settled fraud charges against DWAC the SEC announced on July 20, 2023. That was the action that had kicked off the regulators’ inquiries to begin with. It was rumored early on that DWAC, through Orlando, had had discussions about a proposed TMTG merger in contravention of SEC SPAC rules.

According to the SEC order, in mid-February 2021, a representative of TMTG approached Individual A (Orlando) about a potential deal between SPAC A (Benessere Capital Acquisition Corp., managed by Orlando) and TMTG. A letter of intent was signed, but as it neared expiry, an officer and two board members of Benessere objected to the merger. The matter did not end there. On April 8, Orlando began exploring “Plan A” and “Plan B.” Plan A involved further attempts to complete a merger between Benessere and TMTC. According to the SEC:

On or about April 24, 2021, Individual A [Orlando] learned that there was an opportunity for him to obtain substantial control over DWAC. A few days later, Individual A [Orlando] signed a [sic] LOI with Investment Bank under which he would obtain 90% ownership of DWAC Sponsor [ARC Global Investments, LLC}. Individual A [Orlando] met with TMTG’s representatives the next day and continued discussions with TMTG about a potential merger shortly thereafter.

On May 14, Orlando and the investment bank executed several agreements. Orlando became the 90 percent owner of ARC. At around this time, he became CEO and Chairman of DWAC.

The deal was done. On May 26, DWAC filed its initial registration statement on Form S-1. Unfortunately, the negotiations that had brought it to fruition were illegal. In the end—in July 2023, as we’ve seen—DWAC accepted a cease-and-desist order and agreed to pay an $18 million fine.

A month earlier, in June 2023, the SEC sued Marcum LLP, DWAC’s auditor, for “widespread quality control issues.” Like Borgers, since 2020, Marcum had more than tripled its number of public company clients. The majority were SPACS; in 2020 and 2021, it audited more than 400 SPAC IPOs. The once modest Marcum became enormous:

In 2020 and 2021, over 860 SPACs completed initial public offerings (“IPOs”) in the United States. Over 400 of these SPAC IPOs were audited by Marcum. In 2019, Marcum had served as the auditor for only 185 public company issuers; by 2022, Marcum was responsible for auditing over three times that number—a total of 575 issuers, the majority of which were SPACs. This vaulted Marcum to the fifth largest public company auditing firm, as measured by number of clients.

Marcum offered to settle and agreed to pay a $10 million penalty, be censured, and undertake several remedial actions, including retaining an independent consultant to review and evaluate its audit, review, and quality control policies and procedures. It also agreed to abide by certain restrictions on accepting new audit clients.

At the same time, the PCAOB announced a settled disciplinary order against Marcum, imposing a $3 million civil money penalty in addition to the $10 million imposed by the SEC. It was the largest fine the PCAOB had ever demanded. For good measure, the regulator followed up with an action against Alfonse Gregory Giugliano, the former National Assurance Services Leader at Marcum, “with failing to sufficiently address and remediate numerous deficiencies in Marcum’s quality control system.”

The SEC actions against Marcum meant, of course, that DWAC would need to find a new auditor, who would see to the restatement of the financials audited by Marcum. Marcum sent a letter of resignation to DWAC’s Audit Committee on July 27, 2023. DWAC made proper disclosure to the SEC, as did the auditor. Despite the number of clients Marcum had, DWAC appears not to have had trouble finding a replacement. On August 8, they hired Adeptus Partners, LLC to clean up Marcum’s mess. Adeptus stayed with them for almost another year. On April 1, 2024, six days after the merger was finally completed, Trump Media & Technology Group filed its first 10-K, in which it announced a bad choice:

On March 28, 2024, the audit committee of the Board approved the engagement of Borgers as our independent registered public accounting firm to audit our consolidated financial statements effective immediately after the filing of this Report for the fiscal years ended December 31, 2023 and 2022, which consists only of the accounts of Digital World. Borgers served as the independent registered public accounting firm of Private TMTG prior to the Business Combination. Adeptus, the independent registered public accounting firm for Digital World prior to the Business Combination and the current auditor of TMTG, was informed that it will be dismissed as the auditor of TMTG immediately upon the filing of this Report.

The financial statements revealed the new company to be in trouble. While it had the money that’d been raised for it by DWAC and additional funds from the PIPE investors, its Truth Social site was burning cash and had very few users.

Trump fans didn’t care. Beginning in February, they drove DWAC’s stock price up in anticipation of the consummation of the merger and, two days after the deal closed, took the new DJT to an intraday high of $71.93. It’s now subsided to the high $40s, but still enjoys a market cap in the billions. Short interest is high, and shorting fees are astronomical.

DJT has yet to announce a new auditor, but it’s early. It will be interesting to see who the company chooses, and who chooses to work with the company.

In the meanwhile, observers can keep an eye on the never-ending lawsuits. The latest is a criminal case against Bruce Garelick, Michael Svartsman, Rocket One Capital, LLC, and Gerald Svartsman. In June 2023, they were charged by the DOJ and, in a parallel civil suit brought by the SEC, of trading in advance of DWAC’s October 2021 announcement of plans to merge with TMTG. The Svartsmans pled guilty in April 2024, but Garelick insists he’s innocent. His trial began last week in the Southern District of New York. One of the witnesses against him is Andy Litinsky, the TMTG founder who’s currently suing Trump and being sued by him.

If that’s not enough excitement, there may be more to come from what seems to be an investigation into the funds provided to TMTG by ES Family Trust and Paxum Bank. The Guardian has reported on the matter twice, and last reported on it in early April. It believes “that ES Family Trust operated like a shell company for a Russian-American businessman named Anton Postolnikov, who co-owns Paxum Bank and has been a subject of a years-long joint federal criminal investigation by the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) into the Trump Media merger.”

The Guardian goes on to explain that none other than Michael Svartsman of the insider trading charges is a “close associate” of Postolnikov. Naturally that makes us wonder what may come of a plea bargain that may well have included a cooperation agreement.

First, though, we’d like to know what auditor will next step up to the plate, and what its fate will be.

May 6, 2024 Update

Today, Trump Media Group filed an 8k for a new auditor, engaging Semple, Marchal & Cooper, LLP to replace Borgers.

Semple is https://semplecpa.com. The PCAOB found nothing remarkable in its infrequent inspection reports. But it seems Semple doesn’t have many public company audit clients—only 4 in 2021.

For further information about this securities law blog, please contact Brenda Hamilton, Securities Attorney, at 200 E. Palmetto Park Rd, Suite 103, Boca Raton, Florida, (561) 416-8956, or by email at [email protected]. This securities law blog post is provided as a general informational service to clients and friends of Hamilton & Associates Law Group and should not be construed as and does not constitute legal advice on any specific matter, nor does this message create an attorney-client relationship. Please note that the prior results discussed herein do not guarantee similar outcomes.

Hamilton & Associates | Securities Attorneys

Brenda Hamilton, Securities Attorney

200 E. Palmetto Park Rd., Suite 103

Boca Raton, Florida 33432

Telephone: (561) 416-8956

Facsimile: (561) 416-2855

www.SecuritiesLawyer101.com